8. internet rabbit holes: The Shimmering State and memory

I rely heavily on my Notes app while reading. I jot down feelings, quotes, initial reactions, things I want to look up later — nothing resembling a review, but enough to formulate one later, if I feel like it. When I finish a book, I look back at my jumble of thoughts and settle in for a nice journey down internet rabbit holes. So I thought it might be fun (for me and me only) to take y’all down the hole with me.

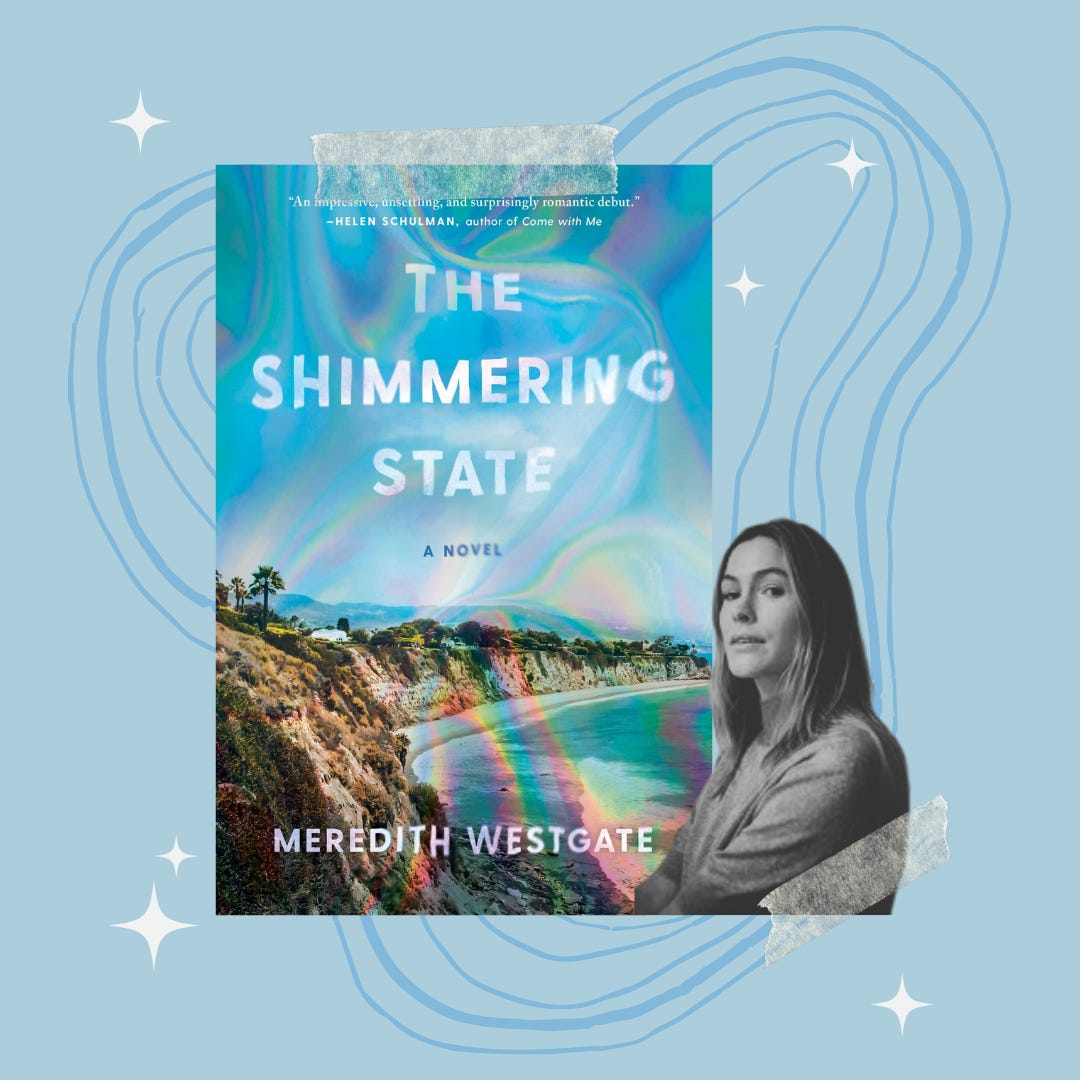

First up we have The Shimmering State by Meredith Westgate, a book that I borrowed from the library as a casual, entertaining read but ended up really reflecting on it. Going to just paste the summarizing part of my insta review here before diving into it because I’m lazy:

In The Shimmering State, Westgate explores the consequences of selectively erasing memories. A new, experimental dementia drug, Memoroxin, reduces our lives — at least, the parts we want to remember — to a tiny iridescent pill. Take your own, and hopefully your brain relearns. Take someone else’s and, for better or worse, immerse yourself fully in their past.

It’s safe to assume that recreational use of a drug that manipulates memory can have devastating consequences. We see that play out through Lucien, swimming in his grief for his mother’s death and his grandmother’s Alzheimer’s; Sophie, a principal ballerina who falls into Memoroxin at the violent hand of another; and Dr. Angelica Sloane, one of Memoroxin’s creators, who runs The Center, a pseudo rehab facility for those who have misused Memoroxin. All are running away from their memories or trying to create new ones that make the pain more bearable, from bodies that remember.

The concept of the body remembering is central throughout The Shimmering State, most obviously evidenced through the characters’ vague but unsettling feelings that there are gaps they can’t fill in their memories — almost like phantom limb syndrome. There is no shortage of literature about this topic, and The Body Keeps Score and The Body Remembers are popular nonfiction books about physical memory, specifically in regards to trauma and healing. I haven’t read either (yet!)

Marcel Proust was one of the first people to note the mind-body connection, which is what gives us phantom memories or makes us physically sick when we’re feeling depressed or anxious. The eponymous Proust effect refers to memories being recalled with external sensory stimuli. This well-known excerpt from Remembrance of Things Past is where this phenomenon comes from — Marcel’s character dips a madeleine into his tea, and the taste triggers a long-forgotten childhood memory:

No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin . . .

I drank a second mouthful, in which I find nothing more than in the first, then a third, which gives me rather less than the second. It is time to stop. The potion is losing its magic. It is plain that the truth I am seeking lies not in the cup but in myself.

And I think this quote of Proust’s also sums the idea up well:

The past is hidden somewhere outside the realm, beyond the reach of intellect, in some material object (in the sensation which that material object will give us) which we do not suspect. And as for that object, it depends on chance whether we come upon it or not before we ourselves must die.

Most commonly, it’s smell that conjures up old memories. Scientists have long understood that smell can be our most powerful sense, and it’s hard to disagree. I still remember the smell of my very first high school boyfriend’s cologne, and if I ever catch a whiff of it in public, I immediately think of him (fondly! We’re still friends). There are other smells we can’t name but are so all-encompassing that they feel like an inherent part of our identity when we experience them — the smell of my parents’ home or my cat’s lil head, for example. And even more, there are smells we identify but can’t ever place, the memory locked away too tightly to reliably recall.

This idea of the body remembering also reminds me of déjà vu, where we recall a memory we aren’t sure we ever experienced, but, we say, we just know we did. It’s an unsettling experience that science has tried and tried again to explain. An interesting theory that’s been posed is that déjà vu is your brain misfiring similarly to how a seizure acts, so it’s possible that people with epilepsy even experience déjà vu just before a seizure.

I always wonder if people today experience déjà vu more often than in pre-internet times because we’re constantly consuming each other’s experiences, most often passively or even unconsciously so we’re never quite sure what our brain has actually digested and will hold onto, meaning we can easily conflate those experiences with our own. We read each other’s thoughts, go on each other’s vacations, attend each other’s weddings — all through social media. I bet you can recall some of your best friend’s memories just because of an instagram post, even though they aren’t yours at all. It almost feels like, in a way, we’re already taking each other’s Memoroxin. Fun!

Our sense of self is distorted by everyone else’s selves, plus the opportunity to continually redefine the self we present to others. We’re constantly sharing our own memories as we’re forming them, and because they have an audience, we want those memories to look a certain way. On one hand, it’s nice to have an easily accessible record of our experiences, which theoretically keeps our memories more reliable — I go through my camera roll almost daily — but we’re also selectively curating memories based on the self we want to perform at the time. Looking back through my own camera roll, I can often see what I was thinking, or what persona I was trying on at the time, and I always note what I missed more than what I captured. The problem with having the power to curate our own memories is that we’re never the reliable narrators we think we are.

In that vein, humans being notoriously unreliable is just another aspect of false memories. In 2020 I read a book, The Memory Illusion by Dr. Julia Shaw, that made me question nearly everything I insist is a true memory — and I already accept that I have a shit memory, so some of y’all who claim to have a good one will have quite the reckoning if you choose to read it (and you should!). The general gist is that because our current experiences are constantly changing our perspectives, they’re also always shaping and revising our memories, making it easy for our brains to blur reality without us ever knowing. Most of our memories are distorted to some extent, and sometimes they don’t even exist at all. For example: some of your most vivid childhood memories are more likely to have been created by the stories your older family members have recounted and baby pictures, no matter how real they feel. This is why you and your sibling might insist on completely different versions of the same event, completely bewildered that the other remembers it their way when you know your memory is the correct one. In reality, both memories are accurate to some extent. Science says humans are essentially incapable of forming memories before ages 3-4, and even then, it’s often a stretch. Your childhood memories are probably not as strong as you feel them to be. Our brains work by forming connections, and sometimes it’s going to make some where there are none.

As is explored in The Shimmering State, the body can remember both fondly and painfully. Both happy memories and trauma make us who we are, but it’s an interesting concept, the question of what you’d do if it were possible to selectively erase or keep certain memories, letting your brain reform those connections where they’ve been lost. And of course, what’s the risk in essentially falsifying our own memories, even if it allows us to take away our pain?

Since memory is so fascinating (and terrifying), there are plenty of movies on the subject as well. The first thing I thought of, and laughed at, was that little mind-erasing thing that Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones flash at people in Men in Black.

And of course, there’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, which I’m sure Meredith Westgate must be a fan of because the story line of Lucien and Sophie in The Shimmering State seems heavily influenced by it (I should probably google this because I bet she’s mentioned it in an interview, or at least Official Reviewers have).

Other movies that came to mind, and I’m sure I’m missing plenty because I’m not a movie person: Memento, Minority Report, 50 First Dates (lol), and the pensieve in the Harry Potter series.

Other links I enjoyed during my rabbit hole:

The author’s instagram, obviously

This lithub piece from MW speculating on what Proust’s instagram grid would look like, which I didn’t see until after I’d rambled about Proust, so hey at least I was on the right track. It’s another meditation on self in the social media era, which I know plenty of people are tired of, but it is something I think about quite literally always (see above), so I enjoyed this a lot.

La Sylphide, the ballet in which Sophie is lead as the sylph, is one of the world’s oldest surviving ballets and was first performed in 1832. A sylph is, apparently, an invisible, nymph-ish being of air.

Sophie carries around a copy of Martha Graham’s autobiography, Blood Memory, referencing it obsessively to calm herself. Graham’s explanation of “blood memory” is something akin to generational trauma, how we “remember” the experiences of our ancestors.

I was thrilled to discover that Chateau Marmont, the celeb hotspot restaurant Sophie works at, is real, though I’m not seeing it on deuxmoi!

The mention of Pioneertown, Calif., which maybe kind of just a Western movie set, is also real.

Speaking of west (sorry), I ended up reading a bit about the show Westworld, which I watched maybe one episode of back in 2016 but didn’t stick with. While not explicitly about memory, I see a connection to The Shimmering State through the playing out of fantasies, selectively choosing our experiences, and the extremes of the human mind.

This scientific article, which I originally saw in a goodreads review and cannot vouch for the validity of, taught me that memory-editing science is actually, terrifyingly, a thing. The drug Memoroxin seems like a ridiculous concept, but maybe we’re not too far away from the ability to selectively change memories ourselves.

That’s all, but I have plenty more where this came from. My brain is an endless well of word vomit and google searches. As always, thanks to anyone who even briefly skimmed this — I know you have better things to do with your time, and yet here you are. And even though most of you are friends I text regularly anyway and once I bribed y’all to finish reading with the promise of a $5 venmo (hi Haley), it still means a lot that you’re here.