internet rabbit holes 4: The Age of Innocence

A deep and pointless dive into The Gilded Age and Edith Wharton's novel The Age of Innocence

In January I read (only somewhat of a re-read) Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence. I loved it. I think about it regularly. There is something so special about a century-old book that is able to not only coexist alongside modern literature but remain relevant. Even in societies centuries years apart from each other, human nature is unflappable.

This novel is 104 years old, and it won the Pulitzer; anything important to be said about it has been spoken again and again. But because I can’t ever leave anything unacknowledged, I thought a more appropriate venture would be another internet rabbit hole through the things that piqued my curiosity as I read, with my running commentary because I never shut up.

I’ve tried to keep this history lesson as brief as I can by sticking to the upper echelons of Gilded Age society, though I could do an entirely separate newsletter on the working class. Even still, this newsletter is past the email length limit. If you’re reading it in that format, be sure to open the full version. Or just save yourself and don’t!

This is so long because I personally knew embarrassingly little of this time period, and it’s possible one of you can relate. My first stop is always the Wikipedia page, and this novel was no different.

The Age of Innocence was published in 1920, but it’s set in the late 1800s — around the same time as Middlemarch, another favorite classic of mine, which made Wharton’s brief mention of it an utter delight.

Edith Wharton was herself a member of the upper class (according to Wikipedia, the saying “keeping up with the Joneses” is in reference to her father’s family; Edith’s maiden name was Jones), which gave her the authority to write about high society. Though she appeared to scoff at many of society’s norms — and New York City itself — she certainly still benefited from her inheritance and geography. Even if her nickname was Pussy Jones, this New Yorker profile from 1929 shows us that she turned out just fine.

Why the 1870s, though? Wharton said of the childhood nostalgia that compelled her to set her novel back in time: "a momentary escape in going back to my childish memories of a long-vanished America... it was growing more and more evident that the world I had grown up in and been formed by had been destroyed in 1914."

Americans have always been unable to reconcile the comfortable perceived innocence of their past with the uncertain changing landscape of their present. This is partly why The Age of Innocence is so compelling, even now, though old money’s disdain of new money isn’t quite as exaggerated today. Its fictional upper class is clinging to the security of their past, one in which they felt their privilege was secure.

Even the assumed origin of the book’s title, a painting, reflects a nostalgia for childhood: A painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds called “A Little Girl” came to be known as “The Age of Innocence.”

The Gilded Age, roughly from the 1870s to 1900, was a time of change and dichotomy, and I can imagine that for many accustomed to their wealth, that change felt like a threat. It was the time of railroad tycoons and robber barons. Many of the US’s most well-known families — the Vanderbilts, Rockefellers, and Carnegies, to name a few — rose to prominence in this era. The History Channel’s page dedicated to various Gilded Age topics of interest is very informative and cleanly laid out.

Going into The Age of Innocence, I only remembered the period as one of rapid economic growth that enticed many to immigrate to the US — highlighting the chasm one had to leap over from poverty to riches. Mark Twain coined the term “Gilded Age” to mean that the glittering surface of society was only masking the country’s sinister underbelly of inequality.

It’s easy to romanticize ornate architecture and fashion, or gawk at social decorum that seems impossible to navigate (this TikTok account covers many, some of which were included in The Age of Innocence, but I imagine Wharton wasn’t writing her book with the mindset of a record-keeper), in the same way it’s easy to laugh at the dumb shit rich people spend their money on today or spend hours diving into celebrity gossip. Both habits I won’t comfortably apologize for, but it’s easy for your eye to catch the shiny surface and miss the rot underneath.

Wharton’s novel glosses over the fact that The Gilded Age was, ultimately, an era of corruption and greed that granted the lucky few opulence at the expense of the masses. I wonder if this oversight is because Wharton didn’t have the benefit of hindsight that we do now, or because her writing was more a documentation than a condemnation. She does indeed condemn high society, but only for what they do to themselves, not to those below them.

European influence

At some point during my reading of The Age of Innocence, I wondered what Europeans were experiencing during the United States’ Gilded Age, given how many of them were immigrating here. Wharton’s characters regularly allude to Europe providing more culture and entertainment. I was struck by how many references there were to New York City being provincial in comparison. Some of those comments might have been for dramatic effect, to take digs at Countess Olenska for leaving her glamorous European lifestyle behind (worth it to escape a monster husband, I’d think), and even more likely is that the barbs were Wharton’s own disdain for the city.

The early half of the Gilded Age roughly coincided with the middle portion of the Victorian Era in Great Britain and the Belle Époque in France.

The Victorian Era was much longer than the Gilded Age, spanning practically a whole century, though it bore some of the same hallmarks: A society defined by class, growing wealth, and rapid industrialization. Britain and Europe as a whole were quite powerful and influential. Much of U.S. culture was inspired by Europe’s, from fashion designers and cuisine to worker strikes and unionization.

(For anyone else like me who wondered “wait, when did Bridgerton take place?” — that was Britain’s Regency era, so several decades before the patina of The Gilded Age settled in)

Belle Époque translates literally to “the beautiful era,” which I’m sure it was, for the wealthy. Similar to Britain and the U.S., France experienced a period of optimism, opulence, and innovation. Worldwide, rich people were just stomping on poor people and wearing a lot of fabric!

European immigrants were eventually lured by the appeal of the U.S.’s massive wage growth, but most were treated like shit when they got here.

New York City in the late 1800s

To the insulated New Yorkers of high society, their city was on the cusp of greatness and domination. Much of the New York we know today came to fruition in the latter half of the 19th century, but The Age of Innocence wealthy folks, both old and new, mostly lived in the Upper East Side and Upper West Side neighborhoods, where a few of their mansions — imagine there being room to build mansions in New York — still stand.

One UWS freestanding mansion sold late last year for $55 million, and, sorry to say, it is spectacular. I gasped when I opened photos of it. And it was originally built for Henry Vail, the editor of a textbook publisher, which also made me gasp because big fucking lol at being able to make that much money as an editor or in publishing.

I’m focusing on homes in New York because this is inspired by The Age of Innocence, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention my home state’s contribution, the destination of many a school field trip: Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, built by the Vanderbilts and still the country’s largest home.

I’ve also been as an adult, and setting aside the gross wealth, it really is a sight to behold — if you’re ever in Asheville (which you should be) I’d recommend taking a tour of the four-acre mansion. That is the house itself — FOUR ACRES — and doesn’t include the even larger grounds, which are now smaller because they sold 87,000 acres to the U.S. National Park Service after George Vanderbilt died.

I love a Wikipedia list, and thankfully there’s one of Gilded Age mansions. Newport, Rhode Island, and Connecticut were also popular locations to build mansions, often as second homes. Some of the mansions in my current home city, Washington, D.C., are now embassies (and one houses the fancy private Cosmos Club), but many of the true Gilded Age homes were demolished long ago, including the ones in New York. The Charles Schwab House (the photo above) has been replaced with a bleak, nondescript apartment building, but at least more than one family can live there now.

These sorts of mansions and townhomes were rare. Outside of the gilded bubble of wealth, much of New York was living in brutal conditions due to the elite’s wealth-hoarding and a lack of housing as the U.S. population exploded. By the time the Gilded Age more or less ended at the turn of the century, and despite the development of apartment buildings, about two-thirds of the city was living in unsafe, crowded tenements.

Landmarks

Central Park as we know it wasn’t complete until 1876, though much of it was built prior. I hadn’t realized, but am also not surprised, that the construction of Central Park meant the destruction of historically Black neighborhoods. There’s no mention of this in The Age of Innocence, of course. They are concerned only with themselves.

Early on in the novel, a reference to the existence of goats in the park caught me off guard. Maybe this is old news to New York residents, but there actually were goats in Central Park, though not entirely of the wild, free-roaming variety I was picturing (though that vibe was what the sheep were for). People took goat carriage rides similar to today’s horse carriages and hosted goat beauty pageants. I laughed, but this is probably where the word “gotham” comes from. They released goats in Riverside Park not too long ago as bleating landscapers, so who knows, maybe the goats will some day get to return to their roots in Central Park.

It wasn’t only Central Park solidified by The Gilded Age; The Statue of Liberty was dedicated in 1886, after years of construction and financing woes, and the Brooklyn Bridge was completed in 1883. The late 1800s also gave rise to the Metropolitan Opera (not without drama!), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the New York Public Library.

HBO’s The Gilded Age

Because I am nothing if not thorough, I started the HBO show The Gilded Age, which is mainly about the quibbles of old money versus new money in New York City during The Gilded Age. Some of it is realistic, some of it is not.

I had little knowledge of the show prior to this internet rabbit hole, but honestly, learning there is a robber baron of a main character named George Russell — my favorite Formula 1 driver to hate — sealed the deal for me. Lo and behold, the opening scene had fucking sheep in Central Park. Like, within the first five seconds. Justice for the goats!

Some of the show is a little too obvious in its desire to point out the distance between the 21st century and the 19th and therefore feels more modern in its language, but its characters are mostly either real people or based on them. I appreciate its focus on old money’s aversion of having to work for your money and its inclusion of racial discrimination post-Civil War. The Gilded Age overlapped with the Reconstruction Era, after all, and The Age of Innocence doesn’t mention it. But white people’s fear of change being rooted in white supremacy and the privilege it bestows upon us is a tale as old as time, so it is somewhat surprising to me that even the most narrow-minded character, played by Christine Baranski, isn’t racist.

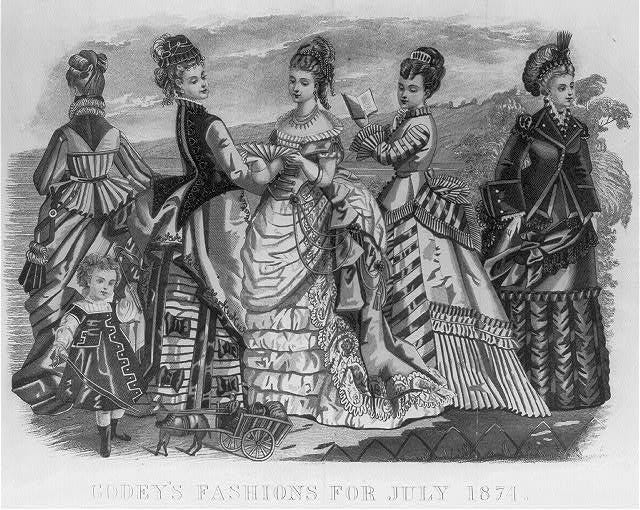

Gilded Age fashion

There are a lot of references to fashion in The Age of Innocence, and particularly of the unspoken rules of fashion that, if followed, kept women in good graces. The Gilded Age show gives us a pretty good picture of fashion, but it doesn’t talk about it so much as simply show us.

The creation of fashion magazines dedicated almost entirely to women’s fashion trends just goes to show how important clothes were to those who could afford to care. Vogue was founded in 1892, in time to chronicle the emerging fashions as the century came to a close. These covers from the time are so fun! And Harper’s Bazaar was first published a bit earlier, in 1867.

There was one fashion designer in particular, Charles Worth, father of haute couture, who both understood and decided what wealthy people were wearing in the 1870s-80s: floor-length dresses, bustles, and tight corsets, meaning dramatic silhouettes (cute face slim waist with a big behind??). Long sleeves and high necklines were also in. Thanks to the introduction of synthetic dyes, dresses were often bright and multicolored. Toward the end of the era, big bustles were on their way out — though the volume just moved to sleeves, a la Emma Stone’s wardrobe in Pretty Things.

Upper class women were not bothered by progressive movements that called for loose-fitting dresses without corsets, which even then had been recognized as unhealthy. But what the rich ladies did adopt were “tea gowns,” which did not require corsets because they were not worn around men or in public. Not wearing a corset suggested intimacy, which would have been scandalous.

This movement was broader than just corsets. It was called the Aesthetic Dress movement, which also inspired men’s fashion to become more theatrical but was then associated with homosexuality — think Oscar Wilde, who always supported Aestheticism — because our most obvious hallmark of heterosexuality has always been …boringness.

There’s also TikTok, because there’s always TikTok, for a visual glimpse into what was stylish but also the logistics of getting dressed. The sheer amount of fabric they were required to wear is the oddest part to me — summer in New York while wearing six bed sheets and a corset?

There are plenty of cosplaying accounts, but TikTok user asta.darling is one of the more thorough ones. She doesn’t make much of an (obvious to me) distinction between American Gilded Age and British Victorian fashion, but my understanding is that the latter inspired the former, so the TikToks are educational regardless of geography, and you can see how many layers and ties it took to get dressed — and undressed, just to ruin everyone’s historical romance fantasies. She also has a fun video of a typical tennis outfit.

But what about men’s fashion! In The Gilded Age show, Oscar van Rhijn’s first appearance is in this little croquet outfit that isn’t really doing him any favors on his quest to appear straight. Men’s fashion has always seem confined to suits, at least in the last couple of centuries, but wealthy men’s fashion was still extravagant, just more subtly. They wore multi-piece suits, often with top hats, and they accessorized with sassy facial hair.

Also, “oscar van rhijn sunglasses” was a suggested google search while I was looking for screenshots of his outfits.

Menswear slimmed down as time went on, and most crucially, the tuxedo, originally created for Prince Albert, was introduced! As were outfits for different activities, such as sporting. However, their sportswear could pass for today’s formalwear, which would definitely be a way to get me more interested in sports.

Regardless of gender, these outfits are incredibly complicated, and the trends changed seemingly as fast as they do now. I guess this is why the Martin Scorsese film adaptation won the Academy Award for best costume design.

If, for some reason, you’ve looked at these fashions as a slay, I found this website where you can buy clothes from this era and many more. Honestly, there should be more over-the-top themed parties.

The 2022 Met Gala

Our favorite celebrities, however, are not winning any awards for their interpretations of Gilded Age fashion. As you might recall, the theme of the 2022 Met Gala was “Gilded Glamour.”

At the time, people were plenty critical of celebrities dressing up as rich people who ruined their country, but it’s so much cringier and almost dystopian now. And even setting aside the morality issue, some of the fashion is either bad or just plain wrong — it seems like half of them interpreted The Gilded Age as the 1920s. It is kind of funny to see the uber-wealthy guests of the Met Gala, one of our most obvious symbols of modern class divide, totally miss the mark on one of America’s most obvious symbols of historical class divide.

I know the Met Gala is all about interpretation and creativity, but we are so far removed from the late 1800s that it would have been fun to just see some silly Gilded Age cosplay. At least a few of them wore corsets. And Blake Lively going for literal New York architecture was kind of great.

Martin Scorcese’s The Age of Innocence (1993)

I didn’t want to publish this without watching the movie since it’s critically acclaimed. The film stays quite true to the book, down to some of the dialogue, which I appreciated.

Side note: I did not picture May Welland as Winona Ryder, but it was the 90s, and Winona was everywhere — I always picture her as the angsty cool girl, but she did play Mina in Dracula immediately preceding her role in The Age of Innocence, and Kim in Edward Scissorhands not too long before that. She also won a Golden Globe for her performance, so thank god I’m not a casting director.

The end

Of course, The Gilded Age had to end. The unchecked wealth hit a tipping point, monopolies failed, and the country entered a depression in 1893. As the economy and political landscape crawled its way back to stability, systems were put in place to protect workers, increase equality (obviously, not well!), and remove power from the robber barons that had dominated for two decades.

As The Age of Innocence closes, there are mentions of a new society, with different customs and various inventions that were once scoffed at. They marvel at how a telephone call makes them feel as if they’re in the room with a person, or how a quick five-day trip across the Atlantic is the new norm (it would take me seven hours to get from D.C. to London).

It made me chuckle to see the characters in The Gilded Age fret about electric lights and telephones taking their jobs; it was probably true, but haven’t we all had the same conversations today? We are always rendering ourselves redundant with our own curiosity.

Important inventions of The Gilded Age included telephones, automobiles, electric streetcars, motion pictures, electric elevators, the phonograph, and incandescent lightbulbs. The linotype machine and typewriters changed the industry of print and publishing, and the accidental discover of X-rays led to the first Nobel prize in physics.

I thought The Gilded Age scene of Edison revealing the lightbulb by lighting up the Times building was really lovely. I can’t imagine what it would have felt like to witness electricity on that scale for the first time, and it was moving to see their delight, however manufactured!

Reflecting upon his life’s meaning at the end of The Age of Innocence, Newland Archer notes that the young men of his generation had cared too much about “the narrow groove of money-making, sport and society to which their vision had been limited” and that his daughter “led a larger life and held more tolerant views” because “there was good in the new order too.”

I’d like to think both old money and new money would have reflected on how they treated those they saw beneath them carelessly, though I’m sure they mostly died smothered by their own standards. I’d also like to hope we’ll all recognize when our own personal ages of innocence have reached their end, that we see “the packed regrets and stifled memories of an inarticulate lifetime” and are able to make peace with it all.

Perhaps there was some regret, as many Gilded Age families fell spectacularly and almost all of their wealth has been squandered away. It’s hard to hold onto wealth when it was acquired through greed! Time estimated that 90% of rich families lose their wealth by the third generation. So I looked up how many robber baron descendants are walking amongst us, other than Anderson Cooper.

The Carnegie wealth is no more, despite the famous name, because Andrew famously gave away his entire fortune upon his death, which isn’t a bad way to repent for your sins. According to Forbes, his direct descendants live private lives, without the Carnegie name, and without generational wealth.

As for the Astors, another prominent family, in 2015 what was left of their fortune went to a woman who married into the family because the actual descendant cut his own sons out of his will for … snitching on him for committing elder abuse against his own mother. Anderson Cooper did his own snitching on his people (joking!!) by writing a book about the Astors last year, as somewhat of a follow-up to his book about his own family, the Vanderbilts.

The Rockefellers do still have some wealth, though largely tied up in trusts and financial services firms. The Morgans are the same — you can’t miss the name, but the living descendants are harder to spot (though thank god we have real housewife Sonja Morgan marrying in for our entertainment). They’re all so mysterious online. Fun reminder that while we’re all out here performing our quiet luxury on TikTok, the real heirs and heiresses are enjoying their wealth silently (or just working like normal people), away from the possibility of criticism.

The old money/new money divide might not be as prominent now as it was during The Gilded Age, but we’re allowed to hate all types of money now, so that’s something!

Reading list

Not that there’s any point in getting back on topic after all that, but here’s a list of books to accompany both The Age of Innocence and Gilded Age rabbit holes. They’re mostly just books that I want to read, but if you have any suggestions, leave ‘em!

Wharton’s other novels, including The House of Mirth, The Custom of the Country, and Ethan Frome.

Vanderbilt: The Rise and Fall of an American Dynasty by Anderson Cooper and Katherine Howe, who also cowrote Astor: The Rise and Fall of an American Fortune (both mentioned above)

The Portrait of a Lady and Washington Square by Henry James (a close friend of Edith Wharton)

A Well-Behaved Woman by Therese Ann Fowler, a fictionalized story about Alva Vanderbilt

Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City by Carla L. Peterson (since The Age of Innocence isn’t going to tell you much about the lives of Black people)

The Witches of New York by Ami McKay looks like a fun take on Gilded Age society and morals.

Bonus: Does anyone remember The Luxe YA series?? It was basically Gilded Age Gossip Girl, if I remember correctly, and now I want to reread them for research purposes.

Thanks for reading, and an even bigger thanks if you dragged yourself through to the end of this. As the general disclaimer goes, I am not a historian. I wasn’t even a good history student in school. I am simply someone who asks too many questions and has too much time on her hands, and if any of this is inaccurate or misinterpreted on my part, please correct me, but you’ll have to forgive me for the oversight.

You can read The Lit List’s past internet rabbit holes here, and if you have any requests for future deep dives, comment/email/text/scream.

The Luxe series had me in an absolute CHOKEHOLD when I was in middle school—maybe we should book club them 👀👀👀

I’ve never been to The Biltmore but have been to many of the mansions in Newport, RI, and they are 🤌🏼🤌🏼🤌🏼 as long as you don’t think too hard about the exorbitance of it all. Joan Didion has a great essay on Newport that ties into a lot of what you talk about in this post. It’s called “The Seacost of Despair” lol

I loved this Steph!! What a THRILL it was to look at all those enormous houses. God. To be rich like that 😪

Super fun & thorough, I really enjoyed how you pulled in so many shows and films linking to the book! No stone left unturned x epic journalism on the gilded age! I have never read The Age of Innocence but I want to now!