Sometimes I read a book whose premise is so fascinating that I forget all about why I liked it or any gripes I might have about structure, plot, pacing, style, etc. Cursed Bread was one of those for me.

Based loosely on a suspected mass poisoning in a small French town shortly after WWII, this novel presents a creative version of what happened, told through the eyes of a woman consumed by her desire and its lack of a home, infatuated with her town’s strange newcomers. The novel itself isn’t based much on plot, let alone fact, but that made it all the more ripe for an internet rabbit hole. So today’s substack is the third installation of this sort-of series, internet rabbit holes, all about the 1951 poisoning in Pont-Saint-Esprit.

Disclaimer/reminder that this is simply a representation of the searching and clicking that I personally enjoyed, not a well-researched, fact-checked report. Feel free to correct me if I’m wrong about something, but don’t expect too much!

Pont-Saint-Esprit translates literally to Holy Spirit Bridge in English. The bridge is a half-mile long and was the site of a historical crossing with some religious significance. It’s in southern France, on the Rhône, which makes it the quiet Mediterranean town of dreams. There doesn’t seem to be much to it these days, with a population of around 10,000, though a 700-year-old bridge built by Louis IX’s brother is pretty cool.

Post-WWII, France entered a period of unprecedented economic growth, referred to as Les Trente Glorieuses. Unsurprisingly, these years of post-war modernization weren’t all that glorious in hindsight, leading to skepticism and distrust of the government that had been controlling the capitalistic economy with little regard for citizens or the environment.

The mass poisoning took place on the front end of the 30 “glorious” years, meaning much of the population would have still been feeling wartime effects on their daily lives and only just finding their way back to some sense of normalcy.

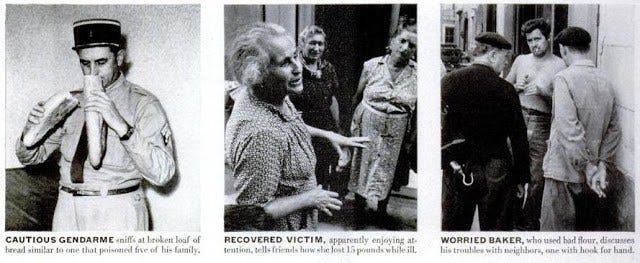

But on to the cursed bread! On a morning in mid-August 1951, around 20 people came down with the symptoms of what we now assume to be poisoning from bad bread — nausea, vomiting, and most alarmingly, acute psychosis. The number of victims continued to rise from there; 250 people were affected, and 50 or so people were hospitalized in asylums. There are conflicting numbers on the internet about how many people actually died, with the lowest being five and the highest a dozen.

Considering that the most popular anecdotes about the hallucinations include an 11-year-old boy who tried to strangle his mother and a man who jumped off his roof thinking he could fly, I don’t blame the doctors for dubbing it nuit d’apocalypse.

The worst part is that there was no treatment for the victims, especially because no one immediately understood what had happened, and many were carted away in straitjackets and locked up in asylums. Some people never recovered, or were unable to go on leading normal lives even if they did. It sounds like many people were truly traumatized, as you can hear from a victim himself.

I’d argue that long-term trauma could be the case to an extent for Cursed Bread’s narrator, Elodie, who intersperses her account of what happened that summer with present-day letters of sort that I interpreted as dispatches from a care home.

So what was it? There are several poisons that could lead to the symptoms experienced — mercury, mycotoxins, and nitrogen trichloride have been floated as the most plausible theories — but what makes this mass poisoning so fascinating is that despite some widely accepted theories in the scientific community, including an “official” one, there are enough voices of dissent to plant a seed of doubt.

The most common and accepted explanation for what happened in the summer of 1951 is ergot poisoning, which comes from a mycotoxin that specifically infects rye and other cereals. Ergot fungus produces alkaloids structurally similar to LSD, so the accounts of hallucinatory symptoms do fit. Ergot poisoning makes even more sense when you look at the government’s monopolistic control of the grain supply at the time (more on that later!).

Mycotoxins are produced naturally by fungi. Exposure to mycotoxins can cause symptoms similar to those experienced in Pont-Saint-Esprit: pain, difficulty moving, delirium, digestive distress, etc. Mycotoxins can cause serious damage in high enough amounts. It’s not to say that you should panic, but it’s not breaking news that breathing in mold spores is really bad for you. HBO just made a whole show about it, and even Studio Ghibli has a movie where spores are the bad guys.

A side note: Mycotoxins have made their way into pop culture, too; the first thing I thought about when I read the word under the Pont-Saint-Esprit Wikipedia page were the rumors circulating back in 2009 that mycotoxins were responsible for Brittany Murphy’s death, the cause of which was ruled to be pneumonia and anemia plus drug intoxication, though the drugs were legal, and then her husband’s eerily similar death six months later.

At the time, those rumors were found to be unsubstantiated, ruled out through toxicology reports and an inspection of their home. Two years after the deaths, Murphy’s mother, whose house the couple was living in, switched her stance to back the mycotoxin theory.

(Mycotoxins can, in fact, cause pneumonia in immunocompromised individuals or those with existing respiratory issues, but we are not here to conspiracy-theorize about Brittany Murphy’s death).

Mercury poisoning was also considered due to the use of a certain fungicide called Panogen that could accumulate in plants grown from treated seeds. The theory was investigated in French court, and though it was ultimately not thought to be the culprit, Panogen was banned in Sweden (where it was manufactured) in 1966 and banned from export in 1970 as a result.

In the 80s, a French researcher suggested it was Aspergillus fumigatus, also a fungus, which most of us are familiar with because it causes aspergillosis in people with weakened immune systems.

In 2008, a historian named Steven Kaplan wrote a 1,000-page book, Le Pain Maudit, in which he suggested that the nitrogen trichloride they used to bleach flour could be at fault. His book got a review in The New York Times, which is much easier than reading 1,090 pages about a mass poisoning that apparently takes 394 pages to get mentioned.

Nitrogen trichloride is more commonly known as chloramine, which is a household name in that it’s essentially the chlorine in swimming pools — the distinctive chlorine pool smell occurs when the compound reacts with ammonia. The smell plus the fact that it’s a highly explosive gas made me immediately skeptical that this was what poisoned everyone, but I am not a chemist and I haven’t read Kaplan’s book!

None of the other poison theories really stuck. Following a train of mycotoxin logic, investigators homed in on the ergot poisoning explanation. They were able to narrow the culprits down to one bread supplier, the Roch Briand bakery.

Due to flour shortages at the time, flour suppliers often cut their products with rye, a practice endorsed by the government’s grain control board, which managed shortages during the war and after. As with any monopoly, quality control was virtually nonexistent, and in this case, bakers did not have any say in the quality of flour they were purchasing from the government.

And there had been prior incidents linked to tainted bread (or rather, tainted flour) in nearby villages. Though symptoms were milder on those occasions than in Pont-Saint-Esprit, both the fateful Le Pain Maudit event and the food poisoning episodes in the weeks prior were all linked to the flour mill of a guy named Maurice Maillet. Maillet’s flour delivery driver received so many complaints that only a few days prior to the poisoning in Pont-Saint-Esprit, he requested that samples of the flour be taken to test for contamination.

Clearly, there wasn’t time for that, but when it came time to launch an official police investigation into the poisoning and they discovered that there were only two possible flour suppliers and one was Maillet, with documented complaints against him, it was fairly obvious who to blame.

Maybe it was a classic case of male ego: Maillet, who had partaken in an under-the-table exchange of grains that was common at the time, thought he could cut corners without reducing quality. Instead, he just gave a bunch of people hallucinations that led to lifelong PTSD among the survivors! He and several of his employees were arrested and charged with involuntary manslaughter.

I am inclined to think that the government’s shoddily controlled supply and distribution was the real villain here, even if individual players are objectively guilty. Conspiracy theories were almost immediately thrown around, as is often the case when the cause of tragedy is both too vague and too much larger than the sum of its parts to satisfactorily find blame, but the most obvious explanation is obvious for a reason. Something something Occam’s razor.

The conspiracies are still fun: The most entertaining alternative explanation is a conspiracy theory that the CIA spread LSD throughout the town as some sort of experiment. And though Sophie Mackintosh’s Cursed Bread never implies this outright (it doesn’t imply much of anything outright), it’s clear with the addition of the character known as “the American” and his supporting-character wife that the CIA theory intrigued the author too.

The idea that the US could have been responsible gained traction in 2009 when Hank Albarelli, an investigative journalist, uncovered an old CIA document with the note "Re: Pont-Saint-Esprit and F.Olson Files. SO Span/France Operation file, inclusive Olson. Intel files. Hand carry to Belin - tell him to see to it that these are buried."

F.Olson is Frank Olson, a scientist who was leading LSD research and working with the CIA at the time, and Belin refers to David Belin, who was the head of a White House commission that investigated the CIA’s abuses worldwide. Sounds too painfully obvious, right? Even the worst police procedural show could solve that one.

To make the storyline even wilder, Frank Olson allegedly died by jumping/falling/being pushed from the window of the 10th-floor hotel room he was sharing with a CIA agent. It was initially ruled a suicide but doesn’t stand as such. According to this account, his death came only a week after he refused to leave the biological weapons program at Sandoz, the only pharmaceutical company manufacturing LSD at the time — and it just so happened to be only a few kilometers away from Pont-Saint-Esprit. (That link also includes some CIA documents regarding his death.)

More shockingly, Olson’s death was nine days after the head of Project MKUltra, an illegal program experimenting with mind control, secretly dosed him with LSD. The aforementioned White House commission (The Rockefeller Commission) that investigated the CIA being shitty confirmed that covert drug studies were conducted on fellow CIA agents.

The reason the explanation that the CIA poisoned Pont-Saint-Esprit feels semi-plausible is because the timing adds up: It’s no secret that governments around the world were experimenting with LSD in the 1950s. The reasons it does not feel plausible are that several symptoms — including intestinal distress — are not linked to LSD use, and it would have been difficult to use bread as a vessel for LSD.

But whether the CIA decided to test out LSD on a bunch of unassuming, war-traumatized, provincial French people or not, it was running a research program called MKNAOMI — thought to focus primarily on biological warfare — with the Department of Defense from the 50s through the 70s. This program is also thought to be the predecessor of MKUltra.

The idea of legitimately using LSD as biological warfare is kind of funny, but I’ll dwell on that so I don’t think about what actually terrifying chemicals and bacteria they were studying — or on Project MKUltra, which surely has a successor somewhere in the depths of hell (or, Langley) today.

I suppose it’s entirely possible that the real explanation for the mass poisoning lies somewhere in between several theories. Both the CIA could have been testing LSD and the French government’s corner-cutting could have led to ergot poisoning. Or maybe my brain is leaning too much into Hollywood! Regardless, given that there are still unanswered questions over 70 years later, it seems more likely that we get a three-hour Daniel Craig-Benoit Blanc mystery than a satisfying conclusion any time soon. Ergot poisoning it is.

I love this - I read this book and my subsequent googling did not go this deep. Those captions are funny - “apparently enjoying the attention” lol

So fascinating!! Makes me wanna read this book and dive into the deep end with you