The alien of the species: women without kids

a review-ish of Ruby Warrington's Women Without Kids turned rant, what's new!

I am not having children. I’m in my early 30s, in a long-term, committed relationship, and I do not want to be pregnant or have children. In a world that feels like it’s on fire and spinning on its axis faster and faster, it’s an increasingly normal decision, one that has spurred Instagram accounts like Rich Auntie Supreme that celebrate and laugh with women who have chosen to remain child-free. (And yet, it’s clearly not the most popular choice considering that the world population is estimated to hit 9.7 billion people by 2050 — if I had a baby tomorrow, it would be younger than I am now when the earth hits this critical point.)

When I share any of this, my words are deliberate, intended to take up enough space that there isn’t room for questioning from those who see me as a foreign specimen and feel a personal responsibility to assimilate me lest the overlords discover I don’t belong. I am not having kids, not I don’t want kids, a declaration I try to deliver with as much confidence and finality as I can. I’m never sure about anything — except for this.

I’m also a reader, and like all of us, I read when I’m feeling most at a loss for words; I let writers find them for me, though the topic of motherhood is an itch I can never quite scratch. So, enter Ruby Warrington’s Women Without Kids, a nonfiction book I had not heard of but requested on NetGalley immediately upon seeing the title and description. I ended up putting it off for months and months. When I picked it back up, it had grown in popularity online amongst mothers and non-mothers alike, even finding itself in the celebrity book club circuit thanks to Dua Lipa’s Service95.

When I finally did finish it last year, I was left feeling both grateful that this book exists within the conversation on motherhood and wondering if it’s actually changing anyone’s lives given the broader capitalistic power structures at play, and the monumental changes to the foundations of our society needed before choosing to have or not have kids ever feels like a liberated choice for women.

I’ve written about this before in a substack about bad mothers in literature, but all women, with or without children, are expected to be mothers in the sense that we are all considered vessels of care. We mother children, yes, but also men, family members, friends, colleagues. We are taught to perform motherhood and its requisite caretaking, as well as mold our personalities into ones that pass a motherly litmus test: kind, patient, selfless.

Not desiring children fails the test, but so does finding motherhood difficult, unfulfilling, or incomplete as an identity. To borrow from my previous newsletter: A woman expressing interests, desires, or opinions outside of her role as mother (and occasionally, wife) is a misstep, a crack in the façade.

Every woman will be expected to take mothering in her stride, without instruction, without adequate support, and without complaint. Any woman who ‘fails’ at this, or who simply opts out, will also have to accept being branded as a deviant and/or defective by those who benefit the most from the upholding of the status quo.

So then, is it really about the kids themselves? It seems more likely that the divide is due to our inability to define women in terms that aren’t inextricably linked with their capability for motherhood. If we are unable to see women as anything but child-bearing and mothering vessels, where do we create space for women who have “failed”?

Online, the women versus motherhood conversation often exists in circles that don’t touch; women without kids talk about being women without kids, and women with kids talk about being women with kids. It creates a positive feedback loop of justification, though perhaps the loop is the only thing keeping us from tearing at our hair and screaming our way through womanhood.

Women Without Kids exists as a positive feedback loop for me, a cisgender white woman without kids by choice. Naturally and as intended — I am the target audience, a woman who has had the privilege of choice, of looking at others’ decisions from afar — but the conversation about having or not having children can’t exclude those who procreate.

And it needs to be mentioned that the conversation around having kids or not having kids is extremely heteronormative; We operate under the assumption that everyone will eventually procreate because we assume everyone either is cisgender and heterosexual or will fall in line and perform within those roles. All of our societal norms are built around the assumption of heterosexuality, including the way we view parenthood.

It’s also often very white, privileged, and upper-class. Being a parent looks different when you can’t afford food or childcare or a second bedroom, or can’t take time off work to show up to appointments and recitals. It looks different when you’re raising a child in a world that won’t treat them like it will treat their white or wealthy peers. And maternal death rates are nearly three times higher for Black women in the US than for white women, and the numbers are already pretty bleak even in the best of circumstances.

As Warrington says in a New York Times interview: “The system is not set up to support mothers. If it’s hard for you, it’s not because you’re weak. It’s not because you failed. It’s because the scales are still so unequal.” Women are told they can “have it all”: motherhood and a fulfilling career and free time, but they will run up against an unfair division of labor and overwhelming expectations every time they try.

I do not doubt that most of those who are already parents can only imagine a bleak world without their children in it, or those who want to become parents feel that their lives are missing something. But to declare that without children, we’ll never know real love or our lives will always remain empty is not only reductive but lacks empathy. It breaks my heart to think of all the women who are waiting for their lives to begin, who are entering miserable relationships with miserable men as a means to the perceived enlightenment of motherhood.

The false universal truth that our lives aren’t complete until we have children is unfair to all but especially and ironically harmful to women with kids, who are often expected to bear the larger share of parental care and household labor without being fairly compensated, both financially and emotionally, because the reward in itself is suggested to be motherhood. If women are simply fulfilling their biological destiny, if they are now considered complete, why would we extend resources, health care, and support? Why would they need help in this ultimate state of nirvana? The assumption can be isolating, even deadly, especially for those who do not have access to community-based care.

As is inevitable with any sort of preaching to the choir, there’s ample opportunity for Women Without Kids to lean so far into empowering women to make choices about their bodies that it would imply there are right and wrong choices on a collective scale instead of as individual cost analysis. It skirts the implication that women without kids have chosen to be child-free because of some higher enlightenment, therefore making it our responsibility to free women who are imprisoned by outdated ideals of motherhood.

Women do have responsibilities toward each other, but those responsibilities center on mutual respect and acceptance. Our responsibility is to aim for Riane Eisler’s so-called caring economy — “one that recognizes the enormous economic value of caring.” Our solidarity comes from the acceptance of others and an acknowledgment of the traps we shouldn’t accept. The more we are cared for, the more we will in turn be able to provide care.

And because there is no singular experience of motherhood, a caring economy allows women to care for children, themselves, and each other in the ways they see fit rather than what we’ve deemed socially acceptable. As it stands, we are not being taken care of, and we are not taking care of each other.

The Substack In Pursuit of Clean Countertops, dedicated to dissecting toxic momfluencer culture, has an interview with Warrington in which she describes her concept of The Motherhood Spectrum, where “any one individual's experience, desire, or aptitude for parenthood, will be influenced by a very diverse multitude of factors … which might change their feelings about motherhood or non-motherhood throughout the course of their lives.”

In other words, the desire to become a parent is complicated and personal. As is the desire to not have children, making all the reasons behind it feel irrelevant and not particularly unique. The same concerns are shared by parents and non-parents alike.

There’s genetics and disease and mental illness; the ever-looming stress of money, how expensive babies and children and adult children are, how millennials aren’t buying houses; a crawl toward a society unprepared to take care of its individuals on a larger scale; an uncertain, unstable, and unsustainable political climate, currently highlighted by a genocide we are all just watching, and an unstable environmental climate as well (Personally and perhaps dramatically, my inability to stop imagining my 12-year-old child searching a desert for drinkable water that I absentmindedly let run down the drain only years earlier while doing some useless 10-step skincare routine). All the reasons that think-pieces have cited for years as they hand-wring about declining birth rates, what it means that young people are having fewer children. Some people have kids for the same reasons I don’t, often as an attempt to create a better future or regain control of their realities and do better by their kids than was done by them. Sometimes, it works.

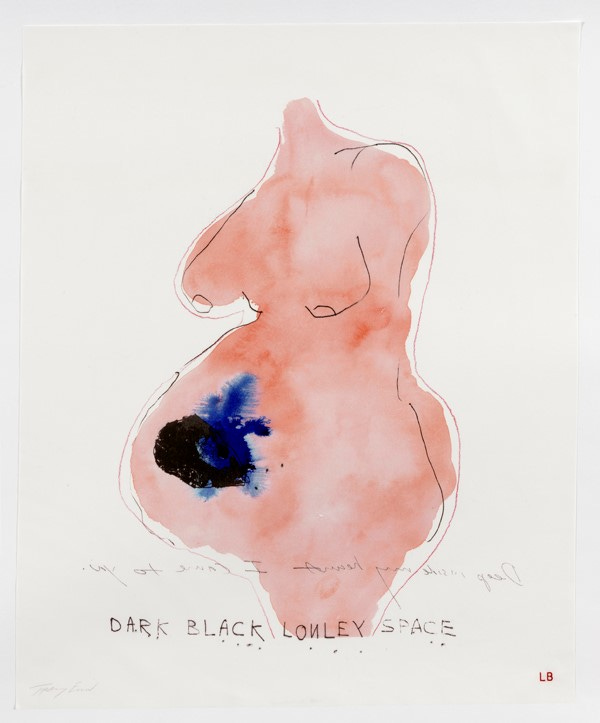

There are also many ways for women without kids to be defined as such, many ways more personal and quiet than mine. None of them require explanation, and being asked to give it can feel invasive to those whose life circumstances have not led them to parenthood and are waiting and hoping, or who have miscarried, who desperately want a child but who do not feel able to parent, who have experienced or are experiencing illness, who are working through or have worked through infertility, who have experienced the staggering loss of a child. The question — do you want kids? — is one I can answer and shrug off but just as often opens up wounds that never have time to heal for others.

Sometimes, the response to I’m not having kids is to convince the non-parent to change their mind by implying that choices about parenthood are stacked in a hierarchy of morality. This suggests that only those who are successful at conception — or who can afford adoption or surrogacy — and then privileged enough to raise a healthy, happy child while remaining healthy and happy themselves are capable of selfless, unconditional love.

It’s most frustrating when liberal women uphold this hierarchy of virtue, with mothers sitting at the very top, because they fail to see how close it is to assigning morality to abortion. And they do it every day, with comments like “I’d never do it myself, but other women can choose” that imply that within this choice — this constitutional right — there are still right and wrong choices to be made.

The politics of making choices while occupying a female body are loaded at every turn, but that’s what parenthood is, for the most part: a choice. Not a more noble or more selfless or more stupid choice; just a choice, with varied consequences like any other. What might feel like an easy choice for one person might have been an impossible one for someone else.

And even still, motherhood or the lack of it is often not a choice. Setting aside the obvious and heavy cloud of uncertainty that is the overturning of Roe v. Wade in the U.S. and the subsequent tightening of reproductive laws, women have been forced into motherhood here — and abroad — for centuries. Parenthood can be a punishment for existing with female reproductive organs. Having a choice at all is increasingly becoming a privilege. To feel comfortable with that choice is an even larger privilege.

Babies are not a salve for the wretchedness of life, no matter how much they are wanted. And when women are forced to have children they didn’t want, those babies can become a burden, babies who bloom into adults who were watered by resentment and guilt and expectations.

In bell hooks’ Communion: The Female Search for Love, we are reminded that we have believed the lie that women are the most nurturing gender to our own detriment and to the detriment of those around us — even our children. The assumption that women are naturally loving leads us to believe that all women want to be mothers and would be good mothers, which not only isolates us but keeps us from holding ourselves and each other accountable when we cause harm or validate gender essentialism. Women aren’t more nurturing, and men are not less emotional, less suited to parenthood; they were raised to be.

And in turn, we don’t always hold men accountable for their missteps — and in some cases, even praise them for missteps that affirm their “manhood.” We socialize girls to be caring and boys to become strong and independent. How convenient that patriarchy keeps men at the top by holding women to a higher standard for compassion.

There are good mothers and bad mothers, just as there are good and bad fathers. The difference is that we allow fathers more freedom to define themselves outside of their roles in parenthood and partnership, giving them a nuanced gray area outside of the black-and-white of motherhood.

“The insistence that there is a naturally biologically based world of sex differences is at the heart of patriarchal thinking. Liberal women and men cannot embrace this thinking and perpetuate it without maintaining an allegiance to patriarchy.” -bell hooks

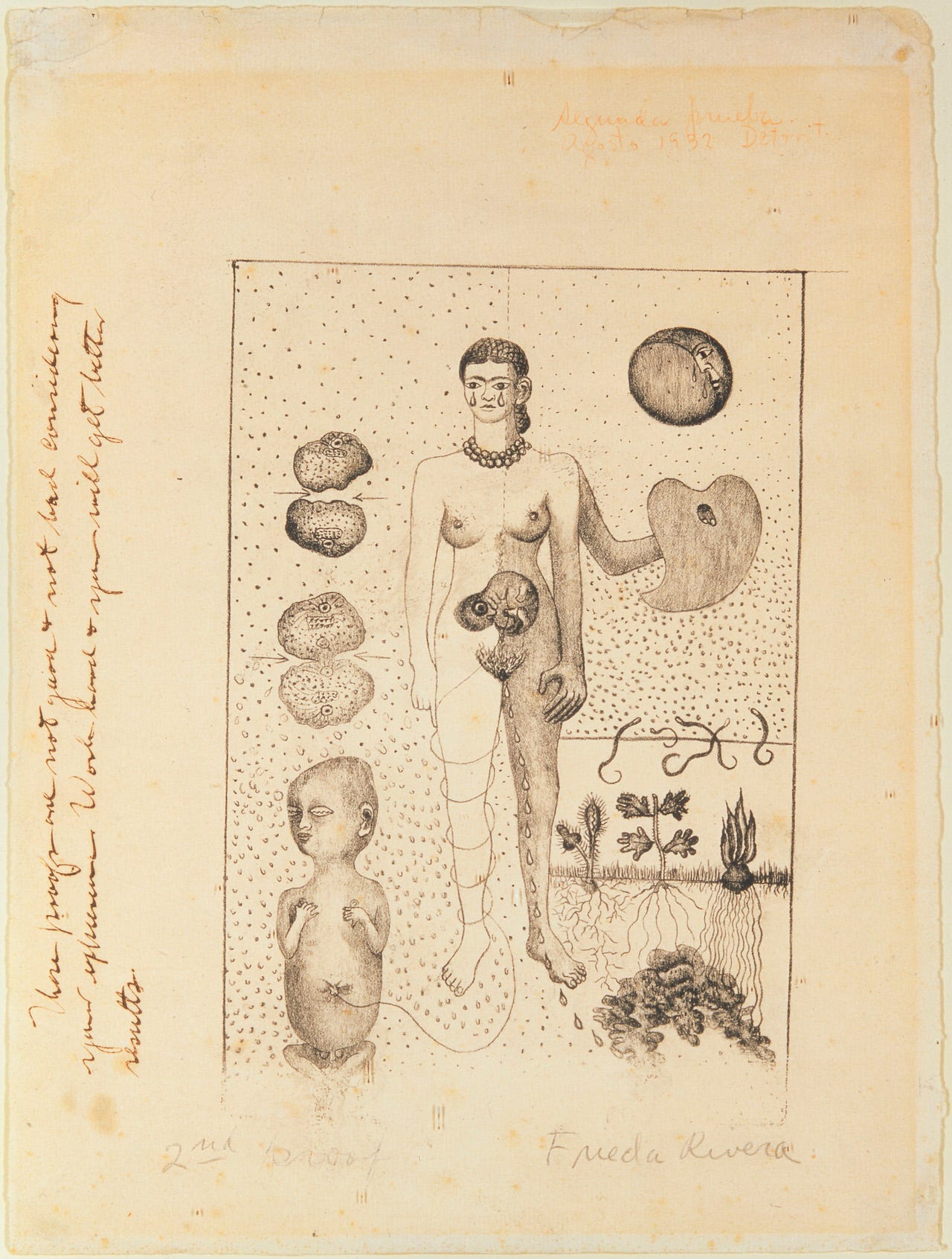

In Women Without Kids, Warrington questions whether her rage and frustration with the expectations thrust on women were hers to begin with, “or had it, in fact, belonged to all the women of my ancestry, all women everywhere, whose bodies, whose mothering, and whose choices have been so manhandled under centuries of patriarchy?”

We carry the joys and sorrows of our mothers and grandmothers alongside our own joys and sorrows, and we’ll pass them down to the next generations. Women who have kids shoulder more responsibility to do better by their mothers and grandmothers and aunts and sisters in the act of raising their children. Mothers need the freedom to be individuals, full of both joy and sorrow; it allows them the space to love better and more responsibly.

Just as pitting men and women against each other does, categorizing women’s primary identities as “with kids” and “without kids” reinforces the idea that women are first and foremost caretakers, not individuals. It’s patriarchal thinking that leaves mothers without the resources and support they need to shoulder their responsibility without it swallowing them whole.

Women Without Kids attempts to but doesn’t quite escape the easy trap of dichotomy, of the labels “mothers” vs. “non-mothers,” that the patriarchy has steadily enforced, often through the help of women themselves. So many of the parameters of womanhood are defined in relation to others: who we are similar to, who we should be and who we aren’t, who we care for. Womanhood and therefore motherhood becomes a competition, though I think by now we all know we cannot win.

I hate the divide, one I have felt so acutely as my friends start to have babies. I hate the feeling that I’m standing at Departures, waving, as they board a plane to their new destination that I am forever denied entry to. And on the other side: Women looking back at a place to which they will never be able to return, the figures on the ground getting smaller and smaller until they disappear entirely.

Contrary to what is often implied when I offer up some mangled explanation, I don’t think my choice to remain child-free is noble, just as I don’t believe choosing to have children is selfless, no matter how much of the self must be sacrificed in parenthood. Either way, it is a choice for ourselves, not others.

I’m lucky in that I’m getting what I want without the complication or heartbreak that accompanies a childfree life for so many, but it isn’t without discomfort. As someone who has always just wanted to fit in, I’ve felt lacking as a woman, wondered if I should just get over myself and procreate, and then hope the love comes later. I’ve worried about a future regret that comes in the form of a biological clock ticking loudly against my chest, like Mona Lisa Vito stomping on a porch.

As Warrington notes, pain or guilt can exist within the freedom and relief of making the choice to not have children. It can exist in the choice to have children, too. Part of our liberation is allowing our decisions to contain multitudes.

It’s painful when it’s implied that my life is and will always be lacking, that I can’t love or feel deeply without knowing parenthood, that I will die miserable and alone in my old age. Sometimes there is a twinge of something I can’t name when I see my partner playing with our friends’ kids, a niggling insecurity that tells me I shouldn’t trust myself or my instincts.

I sometimes even feel uncomfortable when I look at the empty expanse that is my future, no blueprint for what womanhood looks like without children. I feel anxiety when I look at the expectations for women without kids: a successful career, a glamorous lifestyle full of luxury and travel, a busy schedule, accomplishment upon accomplishment now that I have “all this free time.”

Despite knowing that patriarchal, capitalistic standards are responsible for my discomfort, not my choices themselves, it hurts sometimes to feel so different. It’s human nature to seek validation and love; women without kids, women with kids, we just want to feel like one of the few choices we have in life means something, that this one singular choice isn’t the entirety of us.

Women Without Kids attempts to comfort and empower women to assert themselves as they are. It emphasizes that our experiences are universal, no matter how singular they feel in moments of desperation. Warrington also provides an ambitious picture of the kind of society that would need to exist for us to collectively raise children capable of breaking the cycle and creating a world where women’s identities are expansive, where we have universal health care and community resources and sustainable practices.

I appreciate Warrington’s efforts, but it’s difficult to see a point in time where the choice to have children isn’t a loaded one for women and the decision to raise children becomes a collective one. I can only hope I do see it.

Corporate greed becomes personal greed when an instinct for self-preservation morphs into a culture of unchecked self-gratification. Not having kids isn’t going to do anything for society or the planet if the rest of your life is an orgy of competitive overconsumption. (Women Without Kids)

We need more books about women without kids so that women with or without children can learn how to exist in a world that defines them first and foremost as mothers. Women Without Kids is a positive feedback loop for those who identify as such, yes, but it doesn’t condemn women with kids to a life of oppression and disillusionment. Instead, it urges us to shun the “Mommy Binary” in favor of conscious, compassionate, collective care inclusive of everyone.

Ultimately, enacting our duty of care to future generations lies in seeing all families — and all people — as intrinsically interconnected and equally worthy of care. It means seeing all of our children as all of our children, regardless of whether or not we have kids.

Our life trajectories can take endless narrative arcs, pregnancy and parenthood being just one. Many of us are women with kids; some of us are women without. When either of these becomes our primary identity, we don’t allow ourselves or each other to explore and embrace the complexities of personhood. The same gender constructs and societal expectations exist for women with kids and women without. We have to create space for women to be valued as mothers, but just as importantly, to be equally valued without kids.

And we’ll end on book recs, as I attempt to stay on theme with this newsletter:

Motherthing by Ainslie Hogarth, for the desperation for motherhood

The Nursery by Szilvia Molnar, for the dark, isolating cycle of early postpartum motherhood

Sorrow and Bliss, by Meg Mason, for a woman trying to figure it all out

And what’s next up for me on my quest to read all books about mothering and bad mothers and things we don’t want to talk about:

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids

Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder, about a woman who becomes convinced she’s turning into a dog while discovering that motherhood isn’t what she expected. I’m determined to read this one before the movie comes out!

The Push by Ashley Audrain, for when I want my motherhood fiction to be suspenseful and tense.

Motherhood by Sheila Heti, which explores “what is gained and what is lost when a woman becomes a mother.” (side note, why is this cover so different from the original? I don’t like it!)

Without Children: The Long History of Not Being a Mother by Peggy O'Donnell Heffington

This list on bookshop.org called Books that Talk Honestly about Motherhood includes a few titles that have piqued my interest.

And just for fun, some answers you can give the next time someone asks why you’re not having kids and insists on being rude about it:

Why did you have kids?

Your kid’s an asshole. I don’t think the world needs any more assholes.1

Sure, I’ll have a baby — can you send me your address so I know where to drop the kid off once it’s here?

I’m actually busy raising my army of cats.

Do you want to see pictures from my relaxing vacation?

The Lit List is a newsletter on books, reading, and adjacent culture. You can read my monthly Consumption Diaries series here or my internet rabbit holes here, and you can find me on instagram, goodreads, storygraph, or letterboxd to keep up with my obsessive tracking habits in real-time.

A disclaimer that I love all my friends’ babies and none of them are assholes, nor do I think they will become assholes!

Such a necessary read as a man. The bit about whether a woman chooses to have children or not, they are forced to take on a mothering role/responsibility by ultimately mothering someone else—a lot of times, like you mentioned, it’s their partner. Writing like this always serves as a mirror for me. I know my privilege as a man allows me, whether I like it or not, to choose when to step up and step back because truthfully, consciously or unconsciously, my wife will do it. That’s a sad truth I have to fight and confront every day. A lot of men leave their mothers and join other women who become their mothers as well. Thank you for this—this writing makes me uncomfortable and is a reminder I don’t want to be a burden, and frankly, another boy my wife must mother.

I’ve made this about men when it really wasn’t suppose to be about us- my apologies. Grateful for the women in my life, especially Black women.

Wow. Amazing piece. Really resonated with me. The part about the divide between friends having kids and not having kids. I have been feeling that now for so long and not quite sure how to put it into words.